JESUSVILLE

Published May 2011, by Livingston Press.

Available at bookstores, On Amazon and other E-tail outlets

"a truly fascinating and worthwhile book"

----NJ Star Ledger

"The real star here is the haunted, haunting theme park full of crumbling temples, decrepit mangers and mazes of limbless, decapitated saints and Christs--a metaphor for the religious wasteland of the twenty-first century and a complex character in its own right."

---Booklist

"A profound and thought-provoking read."

----Midwest Book Review

"page-turning action scenes"

----Italian Americana

When Joshua Farley—a cult figure searching for an hallucinogenic plant rumored to allow the user to see God—disappears under mysterious circumstances, his disciples gather in the New Mexico desert to await his return. But they aren’t the only ones looking for him and the legendary plant. Other desperate people have also made the trek to this remote section of the world:a disillusioned journalist hoping to restore his lost faith; a small-time hood on the lam from the mob; Farley’s disinherited son; a teenage sexpot who claims to be Farley’s mistress; and a gang of mobsters come to even an old score. They meet in a darkly comic, twenty-first century equivalent of Judgment Day.

Author’s Take on Jesusville: Most of the characters here, in one form or another, have lost faith—in themselves, in God, the Church, or the social order—and so are searching to reclaim what has been taken from them. I wanted to depict the emptiness at the heart of each of them, and the struggle for meaning that results. As their frustration mounts, they turn to more desperate measures and that desperation exposes their vulnerability, their need for redemption, and ultimately their humanity. What better place than the desert to serve as the setting for man’s isolation and seeming inconsequentiality in the face of the universe.

This is a lonely stretch of desert: a wide basin of grey silt, sage and mesquite, forty miles of nothingness between the San Lorenzo Mountains on the west and Apache land to the east. An hour’s drive to the nearest blacktop, two before you’ll hit the Interstate.

No towns here. What you’ll find is an occasional outpost like the one at Indian Point: a cluster of buildings, weathered, flat-roofed, a sagging gas pump out front of the general store, its plate-glass window obscured by beer signs, and next to the store— knocked sideways into permanent slant by the wind—a shed that sold, or had for sale, second-hand tires and automotive parts. Your car breaks down, might as well forget it. Start walking back to wherever it is you come from.

Takes its name not from the Catholic sanctuary at the Refuge of Good Hope nor from the remnants of the now-defunct Holy Land theme park—not even from the Apaches who have come for centuries, once openly and now secretly, to worship their ancestors—but from Joshua Farley, a retired teacher from New York, who came out to “commune with the Lord Jesus.” He dedicated his life -‘till he vanished last year without a trace—to search for a rare species of the sage plant, rumored to grow wild in the hidden canyons of the San Lorenzo’s. The leaves of the plant, according to legend, induce an ecstatic state, thrust you face to face with the living God.

Here the sun beats from skies of the purest blue. In the radiance of day, under its glorious and constant stare, you might believe all things possible, that there is benevolence in the design of the universe. Nights, though. . . nights you lose your faith. Wind tears the surface from moonscapes of sand and rock. Time and space and self dissolve. Darkness unbroken. Darkness so long, so full of eternity, you’d swear morning’s never going to come.

From Chapter One

The priest was still awake—another restless night—when he heard banging on the front door. The clock on his nightstand read 3:15.

He sat on the edge of the bed, thinking his disordered mind must have imagined the sound. Then he heard it again: a slow knocking, the delayed cadence of a tolling bell, rising sharply above the rush of wind. Surely that was no human hand upon the door. Too slow, too unhurried. Not the hand of a traveler seeking refuge from a storm. He wrapped his robe around him and stepped into a hall that led to the common room with its high, beamed ceilings and Spanish oak furnishings. From here it was obvious the sound came not from the front door but from the hill behind the Refuge.

At the window he looked beyond the garden and the walled enclosure. The grotesque facades of Holy Land lifted above the cottonwood trees. He thought a shutter must be hanging loose. Then the banging ceased though the wind persisted, the shutter perhaps broken free, afloat somewhere in the desert air. He would be happy if the entire park blew away. How many times had he petitioned the governor’s office to dismantle it? It was an embarrassment, a nuisance, an abomination.

Inside his room he tried to calm himself but nature’s breath came vicious and snarling against the adobe walls of the building. It hissed in the leaves of the cottonwood trees. For a moment he thought he heard it in the house as well, moving with an intruder’s stealth through the halls and empty spaces. Or was it something else?

Don’t tell me you believe in spirits now, a voice inside his head chided. That’s sacrilege, remember? You’re a man of God. But surely he thought, as he had thought before in his weakest moments, there was every reason to believe this place he lived in was haunted—all those disturbed souls who had passed through here. Yes, they were gone now, the Refuge no longer a rehab center for troubled priests, but they had been here, lived in these rooms, walked these grounds. Surely they had left some of themselves behind: their tainted desires and unsettling urges, their nightmares. That was why he couldn’t sleep. The very air was poisoned.

He had settled back in bed when the banging came again and this time he was sure it was the front door. Twenty-five past three. His new guests weren’t scheduled to arrive for hours yet. He thought perhaps it might be a Farley disciple who’d lost his way. But that was unlikely. The encampment was miles from here, on the far side of the basin. The knocking continued: four or five insistent blows in quick succession.

Pulling his robe tightly around him, he crossed the common room and stood at the heavy oak door. It wasn’t fear that made him hesitate before throwing it open—he had long since lost any fear for his personal safety—but rather the anticipation of an obligation, what might be asked of him. He’d come to believe he had nothing left to give.

The night assaulted him, cold and raw.

The man who stood before him cowered against the wind. Even standing under the porch he had to raise his arm to protect his face and eyes from the biting sand.

“Hell of a night, Father,” he said with a wry grin. He wore a thin leather jacket and jeans and a pair of square-toed riding boots. With his wind-blown hair, his unshaven face, he looked like someone fallen on hard times, a drifter maybe, or someone on the run.

“How can I help you?”

“Shelter, Father. Need a place to stay.”

The priest folded his arms against the chill. He squinted into the mist of sand and darkness for a look at the car parked outside the gate. A dark coupe. Apparently unoccupied. At this distance he couldn’t read the plates. “We don’t normally—we like to have advance—”

“I know, Father, I know. Real sorry to come like this, middle of the night, waking you up. Real sorry, you know? But you see—” He shifted his feet, shoved his hands into his jeans as if to contain his energy, keep it under control. His eyes flared wide and bright in their sockets. “Circumstances, you see? This storm, you see? Things got a little crazy. Got my timing a little screwed up, knocked things off-kilter.” He forced a smile. “See what I mean, Father?”

“What kind of trouble are you in, son?”

“No trouble, Father. Just need a place to stay.” He moved directly under the porch light and offered his hand, his smile broad and white, a playful glimmer in the wild dark of his eyes. He was a good-looking man and he knew how to use that. “Name’s Dillon. Joseph F.X. Dillon. That’s for Francis Xavier. My mother was one of the Saint’s biggest fans.”

“You’re not one of them, are you?”

“Who, Father?”

“The Farley people.”

“Them nuts? Nah, not me.”

The priest feigned a coughing spell to give himself more time. The Refuge had been officially closed for several months now. It was still open to guests, but on a limited basis: parish priests who needed a few days’ rest, members of the laity in search of a spiritual retreat. Both the priests and the laity were typically from the western dioceses, referred by bishops or other church dignitaries. “How did you hear about us?”

“Priest in Abilene. Can’t recall his name. Thought it might do me good, clear my head. Been kinda hectic lately.” “Is that where you’re from? Abilene?” “Just passing through.” Broad smile again—self-satisfied and self-congratulatory. It was charm the man was offering, not information.

The wind rose again. The man on the porch shivered, turning his body against it and pushing his dark hair from his face. He was at least twenty or twenty-five years younger than the priest, about the same height, 5’10 or 5’11, but built sturdier—someone who had spent time in the weight room. Father Martin’s instincts were to deny him entrance. If he was not in trouble, he was trouble itself. Maybe even dangerous. Maybe that, too. There was something—he couldn’t quite identify it: his restlessness perhaps, the hard edge to the energy he gave off—something disturbing about him. But seeing him small and diminished in the wind’s fury, hunched against the backdrop of the desert night, he ignored his reservations, his better judgment. This was a refuge, after all. And he had always been drawn to those in need.

DARK ROAD, DARK END

"A suspenseful eco-thriller."

----Publisher's Weekly

"A novel that provides considerable insight within a fictional context."

---Bookviews

"A fine novel about Florida's illegal exotic animal trade."

----All Things Crime

Walter Morrison, working undercover for the U.S. Customs Service, has been in town less than three weeks but already he’s seen evidence of wildlife smuggling: boatloads of exotic species of birds and mammals being ferried in the dead of night through thefast-running streams of the Everglades.

And what he’s witnessed is only a small part of a vast criminal enterprise that supplies these rare and endangered species nationwide to pet stores, private hunt clubs, wildlife safari parks and even to highly “reputable” municipal zoos. His chance to expose the operation is growing slimmer because someone in his own agency has set the clock ticking on what could be the last seventy-two hours of his life. To complicate matters, Morrison’s a loner. Until now this has been an asset in his line of work, but this job is too big, too perilous to work alone. So he’s forced to depend on an unlikely array of people: a Guatemalan migrant worker here to avenge the death of his sister; a retired Coast Guard Admiral who misses the thrills of his former life; a small-time New York hood on the lam from the mob; and the beautiful and seductive girlfriend of a sleazy hustler. It all plays out in Mangrove Bay. The end of the road. An outpost on the southern tip of Florida, beyond which lies nothing but endless swamp and danger.

I was appalled to learn that the trade in exotic and endangered species is a multi-billion dollar industry. It stands as the world’s third largest organized crime—after narcotics, and arms running. In the state of Florida, it is second only to the illicit trade in narcotics. Despite an international ban on such trafficking, there are many “rogue” nations that do not enforce the ban and that turn a blind eye towards those who violate it. And to be sure, world-wide, there is no shortage of those willing to engage in wildlife poaching and smuggling. One reason for this is the lucrative rewards of such activity—as one U.S. Customs agent put it, “Pound for pound, there is more profit for smugglers in exotic birds [and other wildlife] than there is in cocaine.” Another appeal to the criminal mind is the low risk of being apprehended, this a consequence of the fact that most customs agencies are understaffed and over-worked and must, of necessity, turn their attention to higher-profile crimes, like the trade in narcotics and guns. The way it works is this: animals are poached from all over the world, smuggled illegally out of their respective countries, then shipped thousands of miles via land and sea, and ultimately smuggled into the country of destination. The U.S. and China are the two largest consumers of such contraband. I wanted to shed some light on this situation, to call attention to it and—because I’m a writer of fiction—do so in as entertaining a way as possible, hence the noir suspense/thriller format of this novel.

Morrison stood on the porch of the River Hotel finishing his third whiskey of the evening, wondering how they would kill him. It would be an accident, of course. That was the way with agents who fell out of favor. An unfortunate tragedy of circumstance, a situation that was unanticipated. That would be the wording in the letter to the aunt he hadn’t seen in years. With our deepest regrets. . . .

The whiskey had gone sour on his tongue. Death had never been so real to him. Over the years he had, of course, attended his share of funerals. But his own death had remained a nebulous thing, remote at best, undefined.

Until now.

The realization that it was imminent astonished him, as if he’d lived his entire life without regard for its terms and conditions, its limited warranty. As if he’d failed to read the small print of the contract.

Farther down the porch, hotel guests gathered around a piano bar, the maudlin tinkling music and their chatter of no interest to him now. In this heat even the smallest gesture was an effort, but he waved his glass at the waitress coming toward him, the young perky one—LeeLee or DeeDee—who always offered him a smile.

“Eve-nin’, Mr. M.”

Under the yellow porch lights, his face with its watchful eyes and strong chin, seemed on the verge of discovery. His eyes flicked toward her and he smiled briefly before looking away. Pretty women always made him feel he should apologize. For what, he wasn’t sure.

She took his glass and moved toward the door without breaking stride.

He turned now to the river and the gold disc of the sun suspended above an horizon of slash pine and palm. Usually he didn’t have his fourth whiskey until the sun had set and the sky had turned an iridescent silver. But tonight he didn’t have to wait for the colors of dusk to unnerve him.

When the girl brought his whiskey he moved to the end of the porch with its view of grey bungalows and beyond that, beyond the row of trees with their brush-like blossoms of pink and white, the ball fields of the high school where a handful of Guatemalan boys played soccer. Tonight Emilio was not among them and he felt as if something necessary had been ripped from him. The sons of fishermen and migrant workers on temporary visas, the boys came from the trailer park up river. Watching them at play had been the solace of his evenings.

On the field, the ball arced high, the boys’ cries rising in the darkening air. He took satisfaction in the youthful motion of their bodies, arms swinging freely, brown legs flashing as they followed the ball this way and that across the field. At 51 he could still remember what it was like to be young and he looked back to that time with regret. He wished he could have been carefree and joyous like these boys.

Across the river the swamp grew darker, a chaos of shadow and night sounds. In a matter of hours he would be out there, on patrol again, his nightly ritual. Except that tonight there was a special shipment coming in. Emilio had alerted him to that. The anticipation added to his anxiety, sharpened his fear.

But first he had to meet with Caruso.

He drained the whiskey and turned back one last time to watch the boys, ignoring the romantic notes of the piano and the laughter that drifted dismally in the air around him.

CATHOLIC BOYS

"I recommend it highly"

----Bookviews"

A harrowing tale of sexual

abuse and murder. . .

Aficionados of "Law & Order"

will like this book."

---New Jersey Star-Ledger

"An entertaining story"

----Italian Americana

A character-driven suspense thriller set in the Bronx in 1960. Alex Ramsey, a housing detective grieving for the death of his son, hunts a killer who targets teenage boys.

Published by Livingston Press. Available at bookstores and online at Amazon.com and other e-tail outlets.

Ramsey let himself into his house and stood listening to the silence. The TV’s light glared across the cushions of the sofa. Uncle Milty in a dress and a blonde wig pranced across the screen. It was Helen’s practice of late to leave the set on, without sound. She would rarely sit and watch it, but relentlessly the characters moved in pantomime through a world quiet as dreams. He turned the set off, then climbed the stairs.

At her door, he listened first then knocked. He leaned in to find her curled on her side. The curtains had been drawn tight across the windows. Only a night light offered relief against the blackness. She wanted light when she slept, but not the silver-blue light from the street lamps--the color of grave stones, she said--which gave her a cold feeling. He didn’t argue with her when she made judgments like that, just as he hadn’t argued when she decided that it might be better if she slept alone “for a while.”She had suffered so much already he wanted to give her whatever she asked, whatever she thought she needed. In the shadow of his grief, it had been easy to conceal his disappointment at not having her beside him through the night.

She slept with her right hand pressed to the center of her chest.The way the small fist rose and fell with her breathing made Ramsey think of the words from the Sunday prayer mea culpa mea culpa mea maxima culpa. Through my most grievous fault. He pulled the door closed against the gin’s bitter smell.

In the kitchen he made himself a sandwich but when he sat down he left it on the plate and lit a cigarette instead. He was lighting his second cigarette when he heardHelen’s slow, unsteady step and he rose immediately, crossing the living room to stand at the foot of the stairs--in case. We begin in hope, end by adjusting. Where had he read that? He knew enough to turn the living room lamp on rather than the overhead light,just as he knew not to reach too quickly for her arm. When Helen emerged from her room she liked to do so in stages, without harsh light, with a minimum of intrusion. As she descended in her nightgown, her eyes blank and unblinking above her high cheekbones, she managed to look regal, as she often did despite her drinking and he could not easily read her mood, the distance he would have to travel. When he offered his hand she smiled and let him guide her to the kitchen, but once there she disengaged herself. “That awful smoke,” she said.

“I’m sorry, dear. I thought you were in bed for the evening.” He waited for her to sit but she seemed contented where she was, leaning against the counter. He took his seat and snuffed out the cigarette.

“You haven’t eaten your sandwich.” Her tone was mildly reprimanding, almost playful. He thought for a moment a glimmer illuminated her blue-grey eyes that were dreamy in an unsettling way.

“There was a death last night.”

“Yes, I know. It’s been on the news all day.”

“A child--”

“I don’t want to hear the details.” The flat stare she wore like a mask drove the light from her eyes.

“You know I’ll have to be involved in the investigation.”

“After what you’ve--we’ve--been through?”

“As Chief of Security--”

“You can’t. You simply can’t.”

Ramsey’s eyes met hers. “We’ve got to move on, don’t we? At some point?”

“Where?” she said so softly, so helplessly that he came to her and put his hands on her shoulders. She turned away but he held her firmly. “Look at me, Helen.”

She stared at his shirt or maybe her eyes were closed, he couldn’t tell. Then her head fell against his shoulder. “We’ve got to move on,” he said gently, “the both of us.Together or separately. But we’ve got to.” She fought free of his embrace and stood at the sink, staring into the empty basin. “When you left the Department, you should have gone back into law, not Security work. You’re too good for that.”

She was moving into familiar territory. Normally he would have changed the subject but tonight he said, “What makes me too good?”

“You know that as well as I do.”

“No, tell me.”

He knew what she would say--she had been reminding him of this ever since he joined the PD ten years ago, reminding him of it again when he left the Department last year--but he listened to her recital in the kitchen’s silence as if hearing it for the first time. Maybe he would believe it this time, maybe it would help him sort through the confusion and figure out where he was heading. He was educated, she told him, he held a law degree from Fordham, he knew that man was capable of higher things, of yearningsnobler than anything the lowlifes and criminals he chased could even imagine. He’d been a valued member of the City Council legal staff, not someone who hung back with the apes.

The long hours of the day ganged up on him and he leaned toward her, shoulders sagging, hands stuffed in his pockets. You know I was never satisfied being a lawyer.”

“That’s something I’ll never understand.”

“And something you’ll never forgive, either.”

Tears clouded her eyes. “How can I?”

Ramsey wanted to explain, as he’d tried to so many times, that in committee meetings, in paneled offices, he had felt locked away from the world, out of touch: a bitplayer in a massive legal team. He’d come from a line of practical people--his own father had been a refrigerator repairman—who held jobs with a measurable effect. A man is someone who gets things done, that’s what he believed. Someone who moved in the world of real and ordinary people and who managed to make a difference in that world.Keeping the streets in order was such a job. That had given him purpose. But she knew that. So he said nothing.

“How can I?” She turned to the cabinets, opening and closing doors until she found what she was looking for: an unfinished bottle of gin. “Please,” he said. She hesitated, gripping an empty glass. Then she reached forthe bottle and filled the glass--no ice, no lemon--and took it with her, climbing the stairs without looking back.

He slid open the door to the porch and propped his arms on the rail. The yard, a double lot situated on a corner, afforded him a sense of privacy unusual for this section of the Bronx, this neighborhood of one and two-family homes south of Gun HillRoad.

The air smelled of basil and parsley, though in their own garden the grass had grown meadow-high. The hedges had to be trimmed, the flower beds replanted. One of these days he hoped Helen would get back to it. One of these days—he’d been saying that for nearly sixteen months now, as he watched her lose interest in everything: the garden first, then her crocheting, walks in the neighborhood, the poetry discussion group she belonged to at the library, the woman’s club at church.

He smoked a cigarette halfway through, before following her upstairs. She sat on her bed, her back against the wall, the half-finished glass of gin in her hand. “You didn’t call today.”

“I called four times, dear. You didn’t answer the phone.” He had arranged for Mrs. DeLorenzo, one of the neighbors, to look in on her and he told himself again that he had adjusted to her habit of not picking up the phone when she didn’t want her grief violated. He took the glass from her hand and set it down. “Maybe you’re right. Maybe I should think about going back into law.”

He waited for Helen’s voice to break the silence. It was easier when she was blaming him. Then he could blame himself as well. It seemed the simplest way to explain what happened to them. If he hadn’t become a cop, she wouldn’t have been left alone so much, especially at night. She wouldn’t have had to drink to take the edge off her loneliness, even during her pregnancy, especially during her pregnancy when he was out collaring petty thieves and juvenile delinquents and she was left alone with her fear sand her depression. If she hadn’t started drinking maybe Evan wouldn’t have been born the way he was. And if Evan had been normal, he might be alive today, he might not have acted so heedlessly. And if Evan hadn’t died she wouldn’t have had to start drinking so heavily again, would she? The rationale went on and on. It was Ramsey’s fault. It was the lie that kept them from moving on.

He took her hand and held it, examining the pale skin crossed with blue veins,the thin nervous fingers and perfectly manicured nails. What had become of the woman he’d fallen in love with? She let her head fall against his shoulder and the smell of her body lotion quickened his senses. She didn’t stop him when he slipped his hand inside her robe, her skin coo l beneath his touch, his hand rising from her belly and the contours of her ribs to feel the fullness of her breasts. For so long now she had refused to come to their room but sometimes it would happen like this, weeks or even months apart, on the narrow confines of a single bed. Always with the light on, always with the smell of gin on her breath.

There was no room for invention. He lifted the gown from her and she lay beneath him, gripping his shoulders. Her cry was loud and terrible as if he had reached inside her deepest wound to tear it open end to end. One of her hands settled on his face,fingers splayed like a mask, and she pushed hard in a way that forced his face side ward while her other hand, around his neck, pulled him closer.

She moved against him and cried out a second time, a wailing sound that made him shudder. It filled the silence and she cried out again and again. It seemed to him one continuous sound, rising and falling and rising again, gathering in this one place, this one act, all the accumulated sadness of his life. He closed his eyes against the yellow glow of the night light that reminded him of his room as a child, the nights he was sick with fever,with chills, nights so long he thought he would never see real light again

The Bronx Kill

"A gripping novel"

----NJ Star Ledger

"Interesting revelations in this tale of loyalty, lost innocence and redemption."

---Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

"Unique, impressively crafted, and an inherently riveting read from beginning to end."

----Midwest Book Review

"It's the brooding atmosphere that truly packs a punch. Readers will gladly lose themselves in this novel's sense of foreboding."

----Kirkus Reviews

"A taut, tense and atmospheric tale. Richly developed characters and seductive, suspenseful storyline. A truly thought-provoking tale."

----Mystery Tribune

"A compelling web of complex situations and characters. An excellent and exciting read!"

----Readers' Favorite

On a hot August night, five teenage friends challenge each other to swim the East River from the Bronx to Queens. In the attempt, one boy drowns and the body of the only girl among them is never found. The three survivors take a vow never again to speak about the incident. When they reunite five years later, they find themselves at the mercy of the drowned boy’s brother, an NYPD detective, who holds them responsible for his brother’s death and vows to bring them to justice by any means possible. Now, Danny Baker, one of the three survivors, must fight not only to preserve his childhood friendships but to save himself and his friends from the detective’s brand of vigilante justice.

The Bronx Kill

PROLOGUE

August, 1998

Four of them, stripped to their shorts, stood on the riverbank, eyes fixed across Hell Gate at the lights of Queens.

This had been Charlie’s idea. Let’s swim it.

No one protested. Not Johnny or Danny. Not even Mooney, the weakest swimmer among them. No one dared.

No sweat, Charlie said. Can’t be more than half a mile. Can’t be.

Across the river the lights flared, spur-like, diffused, beyond the roiling currents.

Tonight it’s ours. They had tried before and failed. But that didn’t matter. Not this night. Not for this, what Charlie called the grandest challenge of their youth, the ultimate test of their manhood. Let’s do it, he said.

They’d been drinking and their bodies leaned tentatively toward the water. Uncertain. Unsteady. Charlie with the broadest shoulders, the biggest build, the others thin pale shadows of him.

Above them the rush of cars on the bridge lifted into the night like a primal chant.

Come on.

Come on.

Come on.

Charlie stumbled forward, he was no pansy, feet slipping on wet rocks, arms swinging in broken circles, propeller-like, powering him into the waist-deep water at the river’s edge.

Johnny followed quickly, then Danny, mud sucking at their feet. Only Mooney hesitated, watching from the shoreline.

Come on, Charlie shouted. Prove you got some balls. Prove it.

Mooney shook like he was cold. Thin flat chest, flat belly, thin arms and legs—bird-like, delicate—his face tinged with a blush of shame but his body white as bone.

Come on! Charlie said again, this time Johnny and Danny joining in. Three voices shouting: come on, come on, come on.

Charlie came out of the water, talking under his breath to Mooney, jabbing at his face, his chest, his arms. Softly at first, almost playful. Then harder, harder. Grabbing him and lifting him, turning sharply as though he might fling him into the water.

Mooney slipped free. He hung back on the bank, shoulders hunched in apology. Then the girl appeared. Out of nowhere, it seemed. Stepping from the shadow of the bridge. Sun-bleached hair blown back in the breeze, her smile an arc of whiteness in her deeply tanned face. She had a slow, easy way of walking, an offhand way of saying, I’m coming, too. No chance they wouldn’t go now. No chance any of them would chicken out.

They watched her—Mooney less intently than the others: he’d seen her naked before—as she lifted her halter top, unzipped her shorts. In her bra and panties, she stood on the bank, unflinching under their scrutiny, before entering the water, striking out for the far shore.

Charlie leading the way, the three of them surrounded Mooney then, shouting Timmy Timmy Timmy, pulling at his thin arms, dragging him into the water.

Nobody swam in this river. Too dirty. Too dangerous. Too rife with chemicals, disease. Too subject to strong and unpredictable currents. As rough at times as Hell Gate to the south. At night the ship traffic couldn’t see you. You were flotsam, debris tossing in the waves.

But Charlie plunged ahead, swimming hard to overtake the girl, Johnny following close behind, then Danny, and Mooney dead last.

The water’s black grip felt colder than Danny, the youngest of them, expected this time of year; slick and oily, it yanked him downward. When he fought his way to the surface, coughing, spitting through gritted teeth, he turned to be sure Mooney was following—and he was, arms flailing, feet kicking hard, an awkward but determined pantomime of a swimmer. The others, ahead of Danny, were already nothing more than dark blurs on the water, marked now and again, brief silver flashes.

Danny got his bearings then and swam harder, gaining on the others because he knew without thinking it this test of their manhood involved not only making it to the other side but making it there first. It was as much now about her as it was about proving himself to the guys.

Fifty feet from shore the current began to strengthen. He stopped to rest, treading water, gulping mouthfuls of air, watching the pinpoint of a ship’s light gliding by on the river, watching the shoreline glide by too as he drifted southward. Then he was swimming hard again, fighting the current, trying to make up lost ground.

What happened next happened without warning. A wave from the passing ship swamped him. When he re-surfaced, spitting the sour-tasting water, eyes tearing, thinking we’re all going to die out here, he saw Charlie swimming back toward him, heading for shore.

Too rough, Charlie shouted. We can’t make it.

Then Charlie was past him, head down, doing the flawless overhand stroke he’d won medals for. Johnny was close behind, swimming in his wake, face tight with strain as he too headed back.

I can make it, Danny thought. We’re almost a third of the way and I can make it. I

can. I can. No longer could he see any trace of the girl, Julianne—he was in pursuit of the idea of her, his fantasy of her—so he began swimming again, riding the ship’s waves which were less severe now, small rounded hills of water breaking over him.

In a matter of moments, though, he saw Charlie was right. The current swiped him from all sides, held him captive, dragged him southward toward the bridge. It took all his effort to break free, to spring from its grip, to point himself toward shore where they’d left their clothes.

That was when he saw Mooney coming toward him, arms flailing, feet sending back fantails of spray as he labored into the current.

You won’t make it, Danny shouted.

Mooney kept swimming his awkward, blundering stroke. Danny reached out to stop him, grabbing at his shoulders, his neck, the water rising in furious waves around them, everything—Mooney’s slick skin, Danny’s clawing hands, the stinging burn in his eyes, his throat—all of it inseparable from the river’s raging assault; and then Danny stopped reaching for him, slowly backing away from him as the dark water swirled between them.

Treading water, his heart pounding so hard he gasped for breath, Danny watched him struggle to stay above water. He kept his head turned toward Danny. He seemed to be waiting for something. The look in his eyes said that.

Before he began swimming again, Mooney’s face lifted above the river. He was grinning, or so it appeared, his mouth twisted in an odd, unexplainable way as he leaned back into the current.

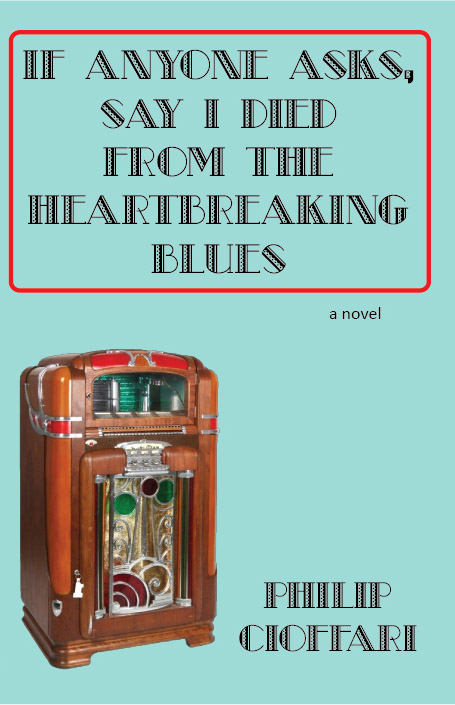

If anyone asks, say I died from the heartbreaking blues

A comic and bittersweet tale of love, longing and coming-of-age in 1960s America.

PART ONE

TRY THE IMPOSSIBLE

The Bronx. June 22nd, 1960

—1—

Joey Hunter, known in the neighborhood as Hunt, turned eighteen the day of his senior prom, the most hopeful day of his young life—or so he believed—because it would be his first date with Debby Ann Murphy.

That morning he waited in his Religion in Society class as Brother Aloysius James, blond hair ascending in waves from his soft pink forehead, clapped his hands to call them to attention. Forty boys, paired into reluctant couples, glared at Brother from either end of the St. Helena’s Boys’ Division basketball court, their faces in the gym’s unflattering light a mix of curiosity, amusement, resentment and outrage.

“Why we gotta do this?” from Kevin Flanagan, his face dominated by little red volcanoes.

“Why can’t we use real girls?” This time the question came from Hunt’s assigned partner, Sal Buccarelli, first string varsity linebacker, known on the gridiron as Sal the Butcher and, in the after-school hours, as leader of a local gang of would-be toughs called the Brandos. Brother Aloysius turned to face Sal of the massive shoulders. “We want you to be ready for them, that’s why. Tonight at the prom we want you all to behave like the gentlemen we know you can be.” And not the hairy apes you so often are, his muttered aside so soft only Hunt caught it.

Brother flicked the switch on the turntable, set the needle delicately on the vinyl: the trombone sound of Moonlight Serenade filled the gym’s barren spaces. Never mind that the big band era had passed, that the boys before him were now dancing to Bill Haley and the Comets, this—Brother believed—was music with elegance and grace. He saw it as his duty to bring civilization to their imprisoned, barbarian hearts. “I need a volunteer,” he called out sharply.

Instinctively he turned to Hunt.

“Oh no, Brother. I’m always the girl. Sal never lets me be the guy.”

With relief, Hunt watched Brother re-direct his attention to Sal. Something about the over-sized, lumbering linebacker and self-proclaimed gang leader—with a face the texture of stucco and eyes the color of an overcast sky—being led around the gym in the feminine role seemed to tickle Brother’s fancy. “Sallie,” he said, using the nickname Sal detested.

“Nah, Brudda. Not me. Not me.”

But Brother Aloysius marched to him, bowed briefly and said in a loud clear voice, “May I have the honor of this dance?” He cupped his hand firmly around Sal’s waist. “Hand on her hip,” he instructed the class, “not where you’d like it to be, ha-ha. Your touch should be firm but gentle. Take her right hand, extend your arm and lead her, glide her, into the music. At the prom tonight, apply the moral standards we’ve discussed in class. Treat her with respect. Treat her like she was your sister.”

A collective groan rose around him.

Brother Aloysius, one eye on the less-than-graceful technique of the boys dancing under the back boards and along the foul lines, confided to Hunt later that waltzing with Sal Buccarelli was like pulling a two-ton truck though a muddy ditch. Hunt could empathize. Being shoved around the dance floor by Sal was like being rammed by a two-ton truck. Mid-song, Brother guided Sal back to Hunt, muttering before he turned away because he couldn’t help himself, “You big oaf.”

Sal directed his response to Hunt, as if he were the source of the insult. “I ain’t no loaf.”

“Oaf,” Hunt corrected him. “He called you a big oaf.”

And for that clarification, Hunt was rewarded with a bloody nose, compliments of Sal during lunch break, as soon as they were out of sight of Brother Aloysius who had cafeteria duty that day.

More trouble soon followed.